On Sunday, I turned 41.

I’ve been told that in “Korean age” I’m 42.

There’s something interesting about reflecting on what happened in the past after I have had a 10+year distance from it.

In my 20s, I listened to a lot of computer scientists’ inspiring lectures. They were world-famous, which gave their words that much more weight. In hindsight, it would have been one thing to learn of their views and to appreciate them for what they were (i.e. views) while quite another to be persuaded by them. For better or for worse, I leaned toward the latter.

In hindsight, there were a few critical reasons why their views had such a big impact on me.

- The vision they portrayed were of a revolutionary caliber with a moral framing of “saving the world.”I have a need to rebel against authority and the status quo. Their vision fulfilled that need. I could not refuse being part of the rebellion—especially if it was framed as a way to save the world.

- Their views also made me feel understood and accepted.Having lived my whole life as a third culture kid, I’d been looking for this feeling from mother/father figures for a long time. When I didn’t get it from my parents, I was ecstatic to get it elsewhere, even if it were from total strangers.

- Finally, I was under the impression that someone had the answer to life.I considered life to be a problem to be solved, and thought that if I can only find that person who has the solution to life, I’d have figured it all out. It just so happened that these computer scientists sounded so confident that I couldn’t help but assume they knew the solution to this problem called life.

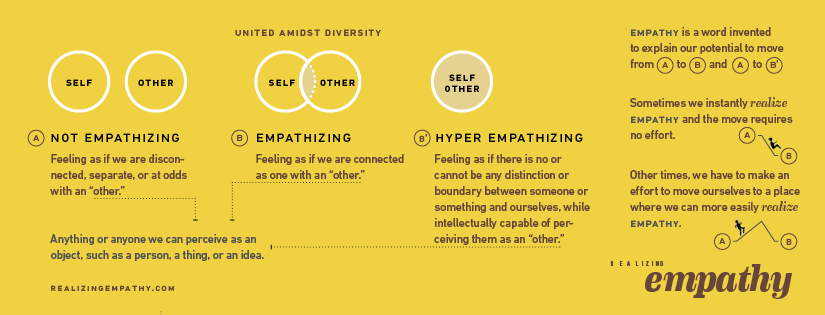

All throughout my 20s, my tendency to hyper-empathize with these influential figures grew larger. As a result, I now understand my 20s as a phase of living their lives not mine. It wouldn’t be until I turn 30 that I realize how easy it is to confuse living someone else’s life with living our own.

Then at the age of 29, I received a challenge. A bewildering challenge at that. One that made no sense. An artist I met at a computer science conference challenged me to go to art school. It seemed like a crazy and irrational idea. Especially because I thought so little of art at the time. I was a man of science, engineering, and design science. Art, I thought, was fluffy, useless, bullshit. In fact, you may have noticed that I put the word “science” next to the word “design” a la Buckminster Fuller, as if to imply that the word design alone was somehow not good enough. “Why would a man of science, engineering, and design science stoop so low as to study art?” was the kind of thought I had back then. (Arrogant much?)

It took me over a year since receiving this challenge of conducting my own, *ahem* scientific, experiments and to gradually build the trust & respect necessary to empathize with artists. When I finally did, it also became clear that this was a challenge I could not refuse. I had to answer the challenge. Why? Because I realized that not answering the challenge meant continuing to live someone else’s life.

Living someone else’s life of rebellion didn’t give me a sense of comfort, but it did give me a sense of safety and that ever-so-desirable feeling that what I’m doing was “important work” that “mattered.” Yet, for better or for worse, I was no longer interested in safety or mattering. I was now interested in being honest with myself in ways I had never been. I was willing to break myself wide open to find out what the hell was inside me instead of continuing to chase after something outside of me because an influential figure had persuaded me into thinking that it was the right thing to do.

For better or for worse, that’s precisely what art and my 30s offered me. It forced me to face my deepest & darkest fears. It crushed every little belief and assumption I had developed over the years. It shook me to my core and took me places I’m both horrified and grateful to have been.

To be clear, I do not recommend this to anyone. I’ll spare you the details for now as I’m not quite ready to write about them just yet. Maybe give me another 10 years.

Above all, I say all this to set myself up to say “thank you” to all those who have stuck by my side throughout my 30s. That’s it really. Because it is through your grace that I’m still alive today both psychologically and physically. I will never forget that.

You know who you are.

May you stay beautiful, always.

with warmth and curiosity,

slim

August 19th 2018

photo credit to Sue Langford