A founder

was feeling burnt-out.

“When was your last vacation?” I asked.

He couldn’t remember.

“I can’t take one.

My employees are working.

I should be there to help them.” he added.

“What emotions do you experience

when you think of taking a vacation?” I asked.

“…Guilt.” he answered.

“Let that sink in.

That’s significant.” I remarked.

He first looked puzzled,

but soon his eyes widened

and he blurted out

“Oh!

I see!

We should all take a vacation!”

…

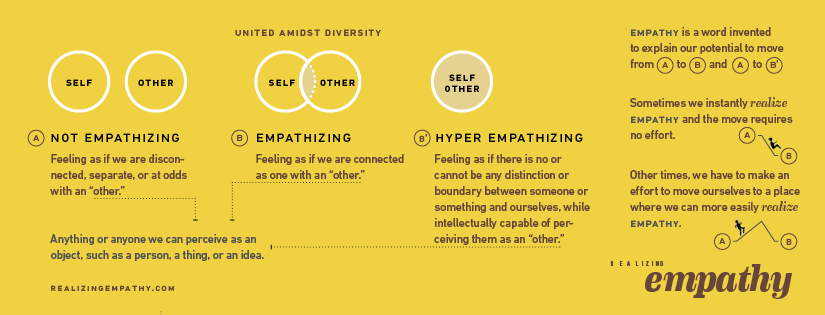

When we feel responsible for “others,”

it’s not unnatural

to feel concern

for their suffering.

With sufficient concern

it’s also not unnatural,

to want

to help.

This is known

as compassion.

Despite best intentions,

however,

the impact of compassion

can also make things worse for others,

and burn us out, as well.

Sometimes,

we need to tame our compassion

to put aside our need to help “others,”

and instead help our “self”

through a vulnerably creative process.

A process

by which we can realize empathy

unexpectedly,

and let emerge

a connected entity

“we”

between self and other.

A process

by which we can learn

a new choice of sight,

that synthesizes

an unpredicted form of help

that helps not other

not self,

but us.